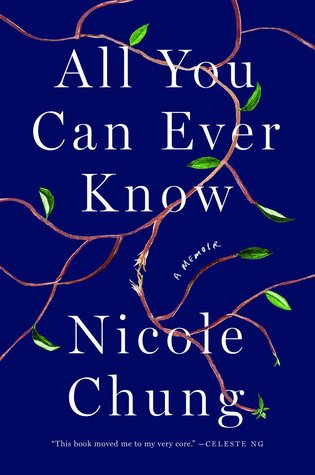

All You Can Ever Know:

A Memoir

by Nicole Chung

Catapult Books, 2018

Reviewed by Barbara Free

After listening to the program, I decided the book would certainly be worth reading. It turned out to be much better than I could have expected. It is extremely well-written, in a straight-forward style. I got the book on a Sunday afternoon, came home and began reading. I ended up staying up way too late because I couldn’t put it down, and finished reading it the next morning! Aside from being a talented writer, Chung has a compelling life story, somewhat different from many adoption situations.

She was born in Seattle to immigrant Korean birth parents in 1981. At that time, her mother already had a teenaged daughter from a prior relationship, and the couple had a six-year-old daughter together and were struggling financially. They also struggled with life in general, and the marriage was rocky. The mother was abusive toward her daughters, particularly the younger one. The father decided his wife could not handle raising another child.

Chung had been born ten weeks premature, and the doctors told them she probably would not live, and that, if she did, she was almost certain to have severe disabilities, such that she might always be an invalid or at least require life-long help. The parents agreed they could not afford such care, or even the hospital bills associated with her premature birth and postnatal care, and the father insisted they relinquish the child for adoption.

At the same time, her future adoptive parents had given up on having a biological child and decided to adopt. When Chung was born, they were told the process would be much faster and less complicated if they went through an attorney, rather than an agency, although the agency had already completed most of the paperwork and home study. They took the advice and hired a lawyer, but the baby was not released to them until she was two months old due to her low birth weight. As it turned out, she was completely healthy, with no physical or other disabilities.

The new family soon moved to a small town in southern Oregon, almost entirely Anglo, so their daughter never saw another Asian person, let alone a Korean. She attended a small Catholic elementary school, where she was sometimes teased and bullied due to her appearance. The teachers did not intervene or defend her, and her parents did not understand how serious the situation was. They were loving and well-meaning, but had no training or education, nor even an awareness of the issues involved in a transracial or intercultural adoption, and told her to just ignore the taunting.

Had they remained in Seattle, of course, she would have seen plenty of Asian people of all kinds, and surely would have attended school with other Asian children. She wondered about her birth family, but was told that they had wanted her to have more opportunities than they could give her, and that God had planned for her to be adopted by her adoptive parents. She did not know that, at one point, her birth mother had, through the attorney, tried to establish some contact, or at least get some information and a picture. The adoptive mother replied that she was fine; they would not send a picture, and she never told her daughter until many years later, when Chung was deciding to search for her birth family.

After some small attempts to search, she backed off, but finally decided to search in earnest when she was married and pregnant with her own first child. She did find her birth parents, no longer together, as well as her sisters. She learned that she had had a much better life, in many ways, than if she had been raised by them, but she had also missed knowing her heritage and culture, and had never had siblings. She became very close to her full sister and her family, and met her birth father, with whom she developed a cordial but not close relationship. Ultimately, Chung decided not to meet her birth mother in person, at least at the time of writing the book.

As she writes of her efforts to establish her own identity, and the sadness of learning the truth about her birth family, she expresses her feelings and thoughts in ways that give this reader new insights, even after having read literally hundreds of books concerning adoption. As a birth mother, reading of her horror at the birth mother’s abusive nature was very difficult for me. I felt great sadness for all the people involved, but great admiration and joy at how Chung handled all of this. She seems to be the kind of person one would really like to know personally.

Various reviews and comments from authors and publications (over six pages at Barnes & Noble) are all positive and, after reading the book, I could not disagree. I plan to read it again, and loan it to any friends with adoption connections. She is a talented writer, and this is an outstanding story. Those without adoption connections could learn a lot from reading it, and those with adoption connections will also gain new insights. Chung is honest about her feelings and she has been able to reconcile her thoughts and feelings with her life experiences in a remarkable, positive way, without glossing over the truth.

Excerpted from the February 2019 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2019 Operation Identity