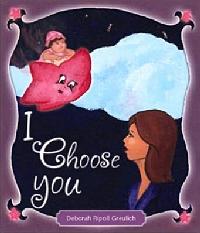

I Choose You

by Deborah Ripoll Greulich

Tate Publishing, 2007

Reviewed by William L. Gage

In the course of updating the bibliography to incorporate books to be published in 2007, I came across a book whose premise I found, to put it mildly, completely objectionable. I might even go so far as to say that it may even be dangerous. The book—I Choose You, a children’s book by Deborah Ripoll Greulich—has a title that might lead one to think that it was written from the perspective of an adoptive parent; however, it is not. Instead, Greulich has turned the story of the “chosen child” completely on its head. In the words of the book’s publisher contained on the book’s back cover:

Imagine a little baby who, before she is born, decides to choose her own parents. Picture her carefully choosing a bright and cozy star and settling upon it to travel the world over until she finds the perfect forever family. ... Once she finds her parents, she travels the world again until she finds just the right birth mother in whose belly she could grow until the day of her birth.

The story of the “chosen child” is a well-known (not to mention well-worn, even threadbare) fairy tale that was created with the intention of making young adopted children feel more comfortable with the idea of being adopted—something of a necessity, given that the majority of children are not adopted—which gained increasing popularity following the publication of Valentina Wasson’s The Chosen Baby in 1939, and whose currency was reaffirmed with the publication of revised editions of that book in 1950 and 1977 (Wasson died in 1959), as well as the promotion of the story by social workers of the period.

Of course, the idea that adoptive parents actually choose their child(ren) is fallacious on its face. The closest one can get to that in reality is when the prospective adoptive parent(s) choose(s) to adopt the child of a particular birth mother (which also typically includes the right of the birth mother to consent to place her child with that individual or family). For that reason, the story of the “chosen child” has limited utility, which it loses as the child ages and asks more-detailed questions about the how’s and why’s of the parents’ “choice” and comes to understand its other implicit deficiencies.

Ultimately, adoptive parents are better served by substituting a story involving a different kind of choice: the choice of adoption as a means of creating a family (whether or not necessitated by infertility, e.g.), along with the corollary choice made by the birth mother to place her child for adoption. This approach casts both choices in the most favorable light by representing them as having been made out of necessity, and as having been made in the “best interests of the child.” In any event, the onus of making choices is placed upon the adults involved in the adoption process—appropriately, since children have very little freedom of choice, especially when it comes to where and with whom they live (as embodied in the old saw that—whether adopted or not—one can choose one’s friends but not one’s family). In short, the adopted child is absolved of any responsibility for its circumstances, or for the attendant emotional pain associated with the process of adoption that may be suffered by the child’s birth and/or adoptive parents.

Conversely (and, in my opinion, rather perversely), I Choose You places the responsibility of “choice” squarely and solely upon the adopted child. Granting the book’s far-fetched premise, you cannot escape the obvious questions. If we were able to choose our families, why would we not choose to be born into them directly, instead of going the unnecessarily circuitous route of being borne by one mother and adopted by another? (In the book, the pre-born child says, “... rather than be chosen to be born into a family, I decided to choose my very own mommy and daddy.”)

Why would we choose to be born to a mother who we know cannot keep us and thereby deliberately inflict upon her the emotional trauma of having to surrender her child (as well as perhaps also requiring another woman to bear the burden of infertility)? How is one to reconcile the apparently contradictory concepts of the “perfect forever family” and “perfect birth mother”? (The book does not address the reason why the birth mother cannot keep the baby she bears, nor why the mother in the “perfect forever family” cannot bear her own child.)

There is likewise no indication made of how the child goes from the arms of the birth mother to the custody of the “perfect forever family.” The child simply appears in a “hospital bassinet” (which, as illustrated here, looks more like the basket in which Moses might have been placed than anything one might see in a hospital) when the adoptive parents come to claim the child.

Any reasonably intelligent child will quickly see through the gaping holes in this unrealistic fantasy, but what about the children who internalize this story and, thereby, the guilt associated with feeling “responsible” for creating their adoptive circumstances and, consequently, the aforementioned emotional pain of both birth and adoptive parents? (This is where I see real potential for harm. One could easily imagine that such internalized feelings of guilt and responsibility might manifest themselves negatively as the child grows up and require some measure of therapeutic intervention to mitigate their ill effect.)

I Choose You is not so much a book as a small booklet, measuring a mere six by seven inches with a saddle-stitched binding. The text is rendered poetically rather than narratively, but the meter is often less than perfect. The color illustrations are suitably simple, but the fact that the characters are white, the adoptive parents heterosexual, and the baby female may limit the story’s appeal.

It is instructive to note that, as stated in its website, Tate Publishing, a self-described “Christian Book Publishing Company,” offers publishing services primarily to first-time authors who “[h]ave ... searched out and submitted [their] manuscript to dozens of publishing companies only to be turned away, time and time again.” The history of publishing is replete with stories of now-highly regarded books being summarily rejected by many publishers, only to finally see print and achieve the acclaim they now enjoy. In the instant case, however, it is easy to understand if Ms. Greulich encountered such resistance by more mainstream publishers, and hard to imagine I Choose You becoming a mainstay of adoption-related children’s literature.

Excerpted from the April 2007 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2007 Operation Identity