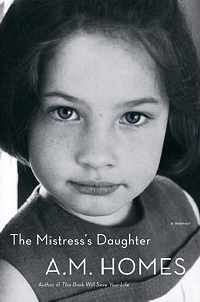

The Mistress’s Daughter:

A Memoir

by A.M. Homes

Viking, 2007

Reviewed by Barbara Free,

Karen Brugge, and Jenna Wiley

I purchased this book, expecting a fresh story about an adult adoptee’s reunion with her birth mother, and possibly her birth father. It was not at all what I had expected. The author, a writer of fiction herself (In a Country of Mothers, e.g.), opens the book with a few pictures of herself as a child and her adoptive family during her childhood. Then it begins with her adoptive parents telling her, at age 31, that her birth mother has contacted them, looking for her. She is upset that they seemed to think they had the right to tell her, or to withhold that information from her. They have already told her adoptive brother (their birth son). They are adamant that they will not tell her adoptive grandmother. Her adoptive mother seems to think it’s all about her—“Think of how I feel. I can’t even tell my own mother. I can’t get any comfort from her. It’s awful.” The adoptive father seems only a shadowy figure in this book.

The author’s birth mother contacts her and tries to meet her, but Ms. Homes is afraid, does not want to see her. She learns that her adoptive parents knew more about her birth mother than they ever told her. Indeed, some of the neighbors once saw her. Instead of agreeing to meet her birth mother, she finds an uncle and parks outside his house. Later, she complains that her mother is stalking her! As the book progresses, she does meet her mother, and her birth father. In fact, she meets with him several times, although secretly. All of the people involved in this story seem self-absorbed, and although her birth mother does seem a bit peculiar, she is obviously a traumatized woman. When the adoptive mother receives word that the birth mother has died, she informs the author in a rather off-handed way. Only some time after her death does the author seem to feel some compassion for her. She seems unsure of her own feelings about both birth family and adoptive family until the end of the book; only after having a daughter of her own (she is vague about those circumstances) does she begin to see herself in the context of those to whom she is related by whatever means.

This book is sure to provoke much discussion by those who read it. I could not, as a therapist and adoption triad member, recommend it as a person’s first book on the subject of search and reunion, as it reports such unsatisfying reunions.

As the book continued, however, I began to like it more, and I loved the last chapter, about her grandmother’s table. A.M. Homes finally realizes that she is a product of four families, and she sees that in her daughter.

Her birth father insists she and he have DNA testing to make sure she is his daughter, but does not give her a copy of the results, and she does not insist on them at the time. Later, she wants the results in order to join the D.A.R. and he refuses to give them to her, although she paid for hers. She also does some extensive genealogical research on both birth family and adoptive family, but does not really seem to connect. She is disappointed that her birth ancestors were not “important people.” She complains that her ancestors don’t know her! (Ancestor—a person from whom one is descended and who is usually more remote than a grandparent [Webster’s Desk Dictionary of the English Language, N.Y., Gramercy Books, 1983, p. 30].) If a person is dead, how could they know about a descendent? In the chapter on research she has done on her adoptive grandmother, she seems to be trying to put herself into that lineage in a biological way. At the end of the book, she mentions having a daughter, but it seems to be almost an afterthought.

There are more questions than answers in this book, and it may leave the reader wondering exactly why she wrote it. I would not recommend this book to either adoptive or birth parents, or adoptees, who are just starting a search or who may be in a difficult relationship with birth or adoptive family.

Excerpted from the October 2007 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2007 Operation Identity