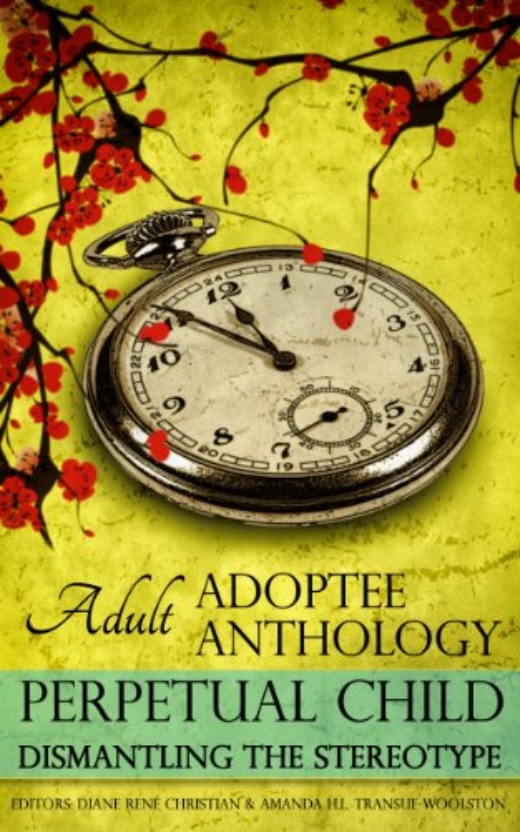

Perpetual Child: Dismantling the Stereotype

by Diane René Christian and

Amanda H.L. Transue-Woolston, eds.

CreateSpace, 2013

Reviewed by Barbara Free & Amy Butel

The title, Perpetual Child, caught our eyes. As we read the various articles, we found several different experiences of adoption, but the common thread was the authors’ frustration and hurt at the way a closed adoption system has treated all adopted persons, no matter their age or circumstances, as children, in that they have been denied access to their information concerning their birth, their birth parents, circumstances, and original documents. Many people have treated them as “cute” or “interesting” due solely to their past adoption.

Presenting life stories has proven difficult for some, especially those who were adopted from a different country or culture, as they have sometimes been seen as curiosities rather than individual human beings, even when they have become professional adults. In such closed systems, particularly where adoption agencies have been involved, not only did the agencies withhold information from adoptees of any age, but also from birth parents, no matter the circumstances of relinquishment, and from adoptive parents.

Some have given “non-identifying” information, but have either not allowed any contact between birth family and adopted persons or adoptive families, or have insisted, even in what they labeled open or semi-open adoptions, that all communication must go through the agency, and any personal contact, if allowed, must be arranged by the agency. Sometimes first names were allowed to be shared, but not last names nor addresses. Sometimes the adoptive parents were given names or information, but birth parents were given no such information. Their attitude was that adoptive parents and their adopted children (even as adults) must be protected from any possible chance of birth parents contacting them, since they were less-than-honorable people, having relinquished this child. Granted, there are circumstances where the child or the adoptive parents needed to be circumspect in their contacts, but most relinquishing parents are upstanding individuals who cannot raise the child for a variety of reasons. Certainly, when the child has become an adult, they do not need an agency’s, nor a state’s “protection.”

The gist of each of the fourteen essays in this book is that adoptees are entitled to their information, and that they need to be acknowledged as normal adults, not perpetual children. Each author also acknowledges that adopted persons have their own thoughts and feelings about their history and circumstances, which they need to work through, and that many need some help with that.

In the first essay, by Amanda H.L. Transue-Woolston, she writes of her feelings and memories of giving a presentation about her life history, as part of her obtaining her degree in psychology. She had done so in undergraduate school, which was supposed to “demonstrate critical self-evaluation skills and a self-awareness.” It had been a negative experience for her. Doing a similar presentation years later, she felt much better prepared, and had more information about her origin, including her birth name, but still was jittery, remembering, among other things, that a classmate had patted her on the head and said, “I had no idea you were adopted. That is so incredibly cute.” At that point, she had the insight that she, as an adoptee, was treated as a perpetual child. She began a quest to explore her feelings and experiences, and those of other adopted persons. When she spoke out about trying to obtain her original birth certificate from the state of Tennessee, she received hateful emails calling her ungrateful and worse. She advocates for ending the attitude of “perpetual childhood” toward adopted persons.

The second contribution, by Nicky Sa-eun Schildkraut, is in the form of a poem, “Everyone Loves an Orphan.” It is written in the second person, the thoughts of an adopted person born in a different culture.

The third, called “Mother May I?” by Lynn Grubb, states that her life as an adoptee is like the game of Mother May I, in which she is the perpetual child and she gets to ask authorities (the government, the adoption agency, and even her mother) if it is okay for her to know herself, and any information she receives depends upon their good will. The way she presents this as a game, with steps forward and back, is very powerful.

The next essay, by Karen Pickell, is about her finding her birth mother’s name and address, through a “search angel” and writing her birth mother a letter, then deciding whether to send it, and her thoughts and hesitation until she finally drops it in the slot at the post office. Her thoughts and feelings, fears and hopes, will be familiar to both adopted adults and to birth parents, as they have approached possible reunion.

The next, excerpts from Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity by Catana Tully, deals with her thoughts and feelings about her family as she thinks about her childhood, her sister, her birth mother who has died, and her own identity as both Hispanic and Black, meeting her birth father, his need to keep his ill wife from knowing the truth, and her decision to communicate with him by letters. This essay can be better understood by reading about the author at the end of the book and perhaps by reading her complete book.

Other contributors offer poems or essays about trying all their lives to be perfect, or risk being seen as an ungrateful adoptee, an angry adoptee, or both. Some felt adoption is akin to slavery, especially when people ask questions like, “How much did she cost?” One discusses amended birth certificates and their required use, as being “forever in a game of Let’s Pretend.” The two male contributors discuss growing up in white families in white towns, and not considered for their own identities as children of color.

Another woman writes about being Chinese, adopted by parents who understood mixed heritage, as her adoptive mother was Danish and Chinese. She was very close to this mother, and grew up in several countries, and discusses her own research into her past as well as her mother’s.

The next-to-last essay is by Angela Tucker, author of You Should Be Grateful (reviewed in the June 2023 O.I. Newsletter). This essay is short but refreshing, as she describes being adopted by white parents, along with several others, and how her parents were “amazing” and how she was treated and respected. She says that many people picture adoptees as children, and have no concept of an adult adoptee, nor that the adoptee’s purpose is to live their own life, not as an appendage to adoptive parents.

The last essay, by April Topfer, is titled “Initiatory Conceptions of the Adopted Individual’s Perpetual Child Along the Adoption Path.” This essay is 35 pages long, much longer than any other. She uses a lot of big words, some esoteric concepts, and her essay is hard to follow, as she talks about “initiatory concepts” and archetypes, and “The Great Mother,” who is “more or less replaceable by a figure playing an analogously affective role.” Neither of us could quite follow her thinking or writing. However, other readers might find her approach helpful.

Taken as a whole, this book offers many viewpoints and experiences. Many will find it enlightening and perhaps affirming in many ways.

Excerpted from the February 2024 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2024 Operation Identity