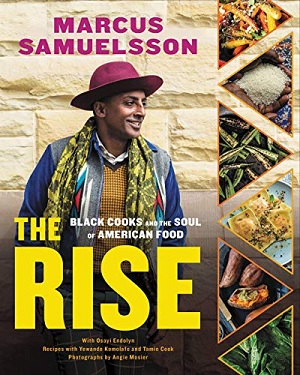

The Rise:

Black Cooks and

the Soul of American Food

by Marcus Samuelsson with Osayi Endolyn

Voracious/Little, Brown, 2020

Reviewed by Barbara Free, M.A.

Samuelsson discusses his adoption story and his immigration, and his choice to live and work in Harlem. He sees his adoption and his immigration as essential parts of his identity. He says, “Being an immigrant and being adopted means being uprooted. For me, it also gave me a different perspective on the United States. I saw the hope that many immigrants have: That whatever is missing or broken where you are, that you can come here to find or fix it.” After reading his memoir, Yes, Chef, one gets a fuller view of how sincerely he means that. He was not only adopted, he was raised by white adoptive parents in super-white Sweden, and he and his sister both from Ethiopia, with very little information about their birth family or country of origin; not because of a closed adoption, but because their mother had died and little was known about her background or the birth father’s identity and background.

This book contains many recipes from all over the U.S., developed by Black cooks of every imaginable background, from Africa, Haiti, the U.S. South, New York, Florida, Cuba, and so on. But it’s not just a cookbook. It contains the life stories of those chefs and relates them to their culture and the overall story of migration, families, resourcefulness, and willingness to try something new. I had seen No Passport Required and enjoyed it; Samuelsson’s energetic personality, unusual clothes, and his great respect for people of all ethnicities and backgrounds, and I appreciated his sharing some of life story, including his adoption. I did not know that he was also a birth father, which he discusses in Yes, Chef. When I heard the NPR interview, I knew I wanted to read this new book, as well as the memoir. They were worthwhile investments. Although I will probably not try many of the recipes, this book is a real joy to read, for his own story as well as the stories of the other chefs.

I did find one small connection to my own ancestors, too. In the Introduction, Samuelsson says,

... Our country was organized to create lasting divisions between us. Those fissures still exist.Some of my Virginia ancestors owned plantations near Richmond—large ones. I have read excerpts from their wills, describing land and possessions, including their enslaved workers. I went to some of those places in 2019 and thought about all their lives and wondered what happened to their descendants. I am not responsible for the past, but I can inform myself about it, and honor those whose names were not listed in the U.S. censuses, some not until 1870. Some of those may be distant relatives, too. I can also see a parallel with the closed adoption system, where people don’t have their information and identity and others think it’s right to withhold information or pretend that adopted persons have no birth family, or to pretend that birth families have no right to know their own offspring or siblings.Here’s an example of how we can see the same piece of this country through two completely different lenses.

A few years ago, I visited a plantation outside of Richmond, Virginia. The nicest family took me around. During the tour, they explained to me, “We do these great weddings here, it’s so beautiful. The weddings are amazing.” My host, a white woman, told me that the land had been in her family for 300 years. She said, “It’s a little bit smaller now—we can only afford to have eight acres. But it was a small plantation, about twenty-five acres.” Then she said, “I want to show you where the workers lived.” Workers. As though the people who were held there had the option of clocking in and clocking out. As if those Black people had the luxury of visiting friends or going away for the weekend.

I was grateful that she was doing this, taking me around her historic land. But her disposition was incomprehensible to me. Modern-day weddings on the plantation—weddings at an enslaved persons’ labor camp? ... I walked around thinking “How can people even live here? How do they survive it?”

I hope this book can be a journey that helps bridge the understanding between those two perspectives.

Samuelsson dedicates the book “to my birth mother, Annu. Thank you for everything you did, and for all the love you gave us in your short life. I love you and miss you dearly. And thank you also to the many other Black women who have remained anonymous but were often the most impactful engineers of the kitchen and true leaders in the culinary arts. ... I am who I am because of all of you. I’m forever grateful.”

If you like to cook or like to eat different kinds of food, or enjoy knowing or learning about various kinds of people, this is a great book, and will give you lots to think about.

Excerpted from the February 2021 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2021 Operation Identity