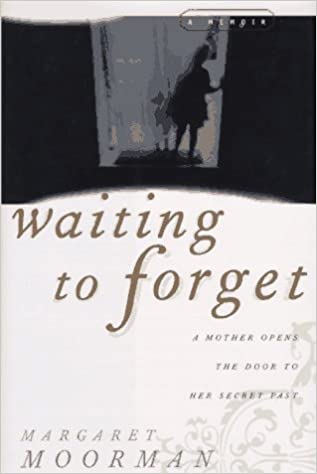

Waiting to Forget

by Margaret Moorman

W.W. Norton, 1996

Reviewed by Barbara Free, M.A.

The summer she was fifteen, 1964, living in Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., she was trying to deal with the unexpected death of her father and her sister’s serious mental illness, which in that era meant a long stay (18 months) in a mental hospital, where she was apparently misdiagnosed. The sister’s illness was a major source of secrecy and shame in the family. Their mother told everyone she was “away at school.” When the sister returned home, Margaret stayed away from her house as much as possible, spending time with friends. Several of her closest friends, with fathers in the military, had moved away in the summer of 1963. Her mother had previously encouraged her (at 13) to get involved with a boy already going off to college, later admitting she encouraged the relationship so that she, the mother, could flirt with him and fantasize!

Later, after a half-hearted suicide attempt, she began dating Dan, who was two years older than she. When her father died of a heart attack on New Year’s Eve, 1963, she was the one who found him. For a long time, she thought that her touching his chest had killed him. She seemed to receive no help for her grief or trauma. Instead she and her sister were called upon to take over cooking and housework while their mother worked at the library. Meanwhile, Dan told her, “I know you’re not a virgin,” although she was, in spite of the previous relationship. When they later did decide to have sex, neither of them knew much about contraception. She’d heard of the rhythm method but didn’t understand how it worked, and thought she was “safe.” Consequently, she became pregnant as a result of this first sexual encounter. However, knowing nothing of the early signs of pregnancy, weeks later, she thought she was just sick. Dan kept telling her the nausea was because she was pregnant. When she had other symptoms, she thought she had cancer. He finally convinced her to go to a gynecologist, so she went to one some distance away, used a false name, and the doctor gave her a prescription for estrogen. She had read an article about “something called abortion,” and asked the doctor if he knew “how I could get a safe one.” He jumped up, threw open the door and told her to get out. Thirty years later, she realized how cruel his behavior had been.

When her mother found the prescription bottle and called the doctor, she confronted Margaret. Dan wanted to marry her and seemed somehow happy that she was pregnant. They made vague plans to marry, but nothing definite. He graduated, then joined the Navy for six months, a program his father thought would keep him out of combat. In 1964, Vietnam was beginning to be an issue. Finally, they told her mother they were going to get married and have the baby. Her response was, “How could you do this to me?,” a common reaction by parents then. Dan’s father also “derided and harangued us,” but his mother never did. Margaret begged Dan to stay, but he did not, and she just became numb. She had just turned sixteen. Feeling she had no support from anyone, especially her mother, she decided to relinquish the baby for adoption. Dan’s parents were relieved. She felt this was what they had wanted all along.

Her mother arranged for Margaret to live at a sort of boarding house run by “a friend of a friend of a friend,” with the cover story that she was “away at school.” They also visited a Florence Crittenden Home, but even her mother felt it was like a dungeon. In a 1965 book on adoption that listed this “home” as a resource, it was noted that, “Negro girls are referred to other sources.” Segregation even in reinforcing shame and secrecy! By the end of the summer, she went to the boarding home, and found it “the happiest, best-run home I have known.” The proprietor, her elderly mother, and her daughter, were kind and non-judgmental. Margaret’s mother would visit but never took her out and Margaret never left the house on her own. She was supposedly in Knoxville with an aunt! She sketched and drew and a teacher from the school system came, who proved to be a resource of information about pregnancy, literature, art, and encouragement, and took her to an art museum and a Greek restaurant, both new experiences. Her mother was horrified. Dan kept writing, mentioning they’d get married and have beautiful children. She knew she no longer wanted to marry him. He came for Christmas and went to see her, took her to an expensive restaurant and they both pretended to enjoy it, but she was no longer interested.

She arranged for her child to go immediately to adoptive parents, so he would not be in a foster home and then moved again. The obstetrician said, “It will be easier to give up the baby if she doesn’t see it.”—common advice at the time, even though it wasn’t true and only served to reinforce the trauma. The doctor and Margaret’s mother decided to induce labor on January 15, so Margaret could return to school for second semester. He told her mother, “Soon, you can put it all behind you,” and then, as an afterthought, to Margaret, “And so can you.” Later, her mother told her the stretch marks would never go away. “They’re permanent!” The modern day equivalent of a Scarlet Letter “A”! She was, indeed, induced on January 15, 1965, put in a labor room with other women under the influence of “twilight sleep,” moaning and screaming. She was untrained, uninformed, and felt abandoned.

Later, she awoke, was told she had given birth to a boy, but not allowed to see him at all. Years later, she learned she had had a traumatic birth, with forceps and many, many stitches. Being terrified as well as drugged, she could not have cooperated in the birth in any way.

She still was given no real medical information, and no emotional support by her mother. In fact, she discovered that her mother had not cleaned out the refrigerator since Margaret had left the previous September! She cleaned the house to channel her feelings, went back to school, and felt out of place. Some of the teachers would not look at her, as if they knew. Her English teacher, however, welcomed her. The first book studied was The Scarlet Letter! She says, “Mr. Shelton smiled encouragingly, ... several times a day, but did not call on me ... until we had moved on to another text.” She was “invited” to speak to the guidance counselor, who tried to draw her out, but was “clearly uncomfortable in my presence.” She did continue to see Dan, who had completed his service and was working to pay her mother $400 for half the cost of the pregnancy. They saw each other at her house, pretending to still have a relationship. She later realized it would never have worked out, due to their differences and his temper. He seemed to think everything was okay and was interested in resuming sex. She refused, outraged and hurt. He went off to college and she had her senior year. He wrote, complaining that she had gone on a date without his permission! He kept telling her he was the boss! She went to his homecoming weekend and broke up with him, and he cried. When she told her mother, she was outraged!

Margaret went off to Connecticut for college, where she kept looking for a relationship that would save her from her own inner self. Finally, she told her mother she needed to see a psychiatrist. After the first appointment, her mother asked her what she had discussed with him and then made her call him to say she wouldn’t be coming back. “There is no way in hell you can make me pay for that crap!” was her mother’s statement.

She transferred to Colorado, then took a year off and worked, then back to Connecticut, now five years after her son’s birth. She majored in art, and met a boy named George her senior year, and they got married the day after graduation. They moved to Seattle where they both went to graduate school, but she could not confront her own issues and left the marriage just as she finished her master’s. She states, “The simple truth was that without confronting my memories I could not become fully formed.” For her, her father’s death was even more primary than her baby’s father’s inability to accept her as she was and her own inability to accept herself. Later, she was involved with a married man, knowing he was not free to commit to her, because he was already cheating on a wife. By that time, she was in New York, 31 years old, half her life since her child’s birth. She entered into serious therapy for several years, but apparently did not deal with the grief and trauma of her pregnancy and relinquishment.

She continued her art career and writing. During those years, she met Harvey, the man to whom she is still married. Two months after she met him, her mother died of a stroke. She took care of the funeral and the estate, made sure her sister was stable, and only then heard about the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, and began attending a siblings meeting. For the first time, she met others with the same issues. She confronted her fear that she, or her son, might become mentally ill, that perhaps she had “damaged genes.” She never consciously worried about her son, but about a possible child she might have and keep. Through this group, she learned that her chances of having a mentally disabled child were no more than that of the general population.

She had married Harvey when she was 40 and felt old, but after the geneticist’s talk, decided perhaps she could have a child. Two months later, she was pregnant. Harvey, who was in his 50s and had a grown daughter, had some mixed feelings. She was afraid she might lose this baby, but did not. She decided not to write about her sister’s illness while she was pregnant. She said she had never felt free to love her son when she was pregnant, but this time she was completely overwhelmed with love as well as worry. Harvey was not excited until he heard the baby’s heartbeat. Because of her age, she had amniocentesis and learned she was carrying a normal female. She confessed to being afraid of labor and delivery and was assured it would be better this time, and she would not be alone. Still, she did no childbirth training or exercises.

Her water broke while she was having lunch with a friend and she went immediately to the hospital. She gave birth to her daughter, Laura, that evening. She could not bear to be separated from her and managed to get her out of the nursery and into her room. By that time, most women had their babies in their rooms all the time. During Laura’s infancy and early childhood, Margaret was overprotective and overly worrying, not wanting the child out of her sight, passing her own anxiety on to the child. Laura got over it, but Margaret did not, even when Laura was in preschool and kindergarten.

A friend, who was also a writer, suggested to Margaret —who had by now published the story of her sister’s mental illness and their relationship—that she write the story of her first pregnancy, in 1965. She protested, but began to see how her anxiety about Laura being “taken” by a stranger related to her son being taken by strangers, his adoptive parents. She began to read about adoption, including about the DeBoer-Schmidt case, and that Concerned United Birthparents was a “secretive, radical organization,” although, in fact, it is a very well-respected group. She went back to her psychiatrist, an adoptive mother.

Fifteen years earlier, she had contacted the adoption agency that handled the adoption, wanting them to put a note in her file that she was willing to be contacted. She was told the file was sealed by the court to protect her privacy. Ten years later, she contacted them again and was told, “The person who deals with birth mothers isn’t here right now.” They did tell her the adoptive parents used to bring her son to their Christmas party, and had adopted a daughter when he was three. They never called Margaret back. Six years later, in 1994, she read The Adoption Triangle, by Sorosky, Baran & Pannor.

These newer books seemed to respect birth parents instead of vilifying them. She learned that most birth parents want to know their children and never forget them. She began to think about her son’s possible feelings about not knowing his biological family nor anything about them. A friend of hers adopted two children and asked her to be their “honorary birth mother,” because she knew her and she felt that was safer than knowing the real birth mother! She learned that in many so-called open adoptions, lawyers and/or agencies recommend that the prospective adopters have a separate temporary phone number for birth mothers and never give them their true names, numbers, or addresses, to protect them from birth mothers. What message does this give their children? Another author emphasized the importance of genetic inheritance (product quality!) and urged that records be open to adoptees but not to birth or adoptive parents! Her justification was the birth mothers would be too shocked, and had probably married and kept her secret, even from her husband. She admits that’s rarely the case, but says birth parents searching “lacks justification,” that their prior relinquishment was made voluntarily and is “forever binding.” Many birth mothers were not adults and could not legally relinquish custody without their parents’ consent, so it was not really voluntary.

Finally, she contacted CUB and was told there was a search and support group in New York, run by Sam Friedman. She learned of the International Soundex Reunion Registry in Nevada, and registered, but found her son had not. She contacted Friedman but did not yet attend. When she finally did, she found there was a charge for each session—$10 for members, $15 for non-members. This was supposed to be a support group, not a therapy group. He told her to use a woman he’d referred her to for search and his group for dealing with her feelings! All the others there were adoptees, mostly angry young males. He emphasized that adoptees feel rejected by their birth mothers and also afraid to upset adoptive parents. He spoke for all of them! She left the meeting with another book, The Other Mother, by Carol Schaefer. She said she wept as she read it, as she saw the parallels with her own story, even the time line. She decided to search and found she could not easily do it on her own. She shut down for a while, did not go back to Friedman’s group, realizing she “hated his controlling ways, hated listening to the adoptees’ complaints.” She met adoptive parents whose children were friends of her daughter’s and was amazed at their attitudes, expressing joy at adopting a full sibling of their first child, saying, “It’s a miracle. We were so lucky!” Lucky that a woman had to relinquish another child? She read an article in New York Magazine entitled “Baby Hunt” [7/26/93], written by an adoptive mother, in which the author described how some states have “good laws,” meaning shorter waiting periods before the adoption is final; and how a birth mother, whose expenses she and her husband had paid, changed her mind and kept her child, saying, “On the eve of her delivery, despite ... our constant attention, the battle is lost.” Adoption and relinquishment are seen as a battle?

She begins writing the book telling her own story, but then tries to back out of it. She is still concerned her son might have mental illness. She placed an ad in a magazine called Reunions, seeking stories from other birth mothers. It turned out to be a guide for planning family reunions, but she did receive several replies. She found that birth mothers were no longer willing \to hide in shame, and that others who had not dealt with their grief and trauma had been overprotective of subsequent children. She finally did search in earnest, with starts and stops and great delays in response from the agency, but finally is able to write a letter with non-identifying information, through the agency, to her son. He was now turning thirty years old. After some time, she finally received a reply from her son, with no name, address, or information about where he lived, saying he wasn’t ready to meet her, and was afraid his adoptive mother “might worry.” Was Margaret going to snatch a thirty year old man from his crib?

The book ends rather abruptly there, with Margaret being ecstatic that she has found her son is alive and that he has “had a good life,” but she still does not know his name or his whereabouts, and has no expectation of ever seeing him in person.

Comments on her book and reviews of it on the Internet ranged from appreciating that she was considering “other people’s feelings,” to birth mothers who could not believe she was satisfied with one letter, not even revealing his name or address, nor any plans to meet her in person. One wonders, since she has apparently not written anything else about adoption, where they all are now, in 2022, when he is 57, she is 72, and her daughter is 32? We could find no information, other than she is still married to Harvey and lives in New York State.

This article started out to be a simple book review, but struck this writer’s nerve, as another birth mother. Although the book is not new, the story is still relevant, and a birth mother is always a birth mother, whether she is reunited with her relinquished child or not. One hopes that the author has dealt with her feelings, her grief, and her needs in more depth now than she seemed able to do when writing the book.

Excerpted from the July 2022 edition of the Operation Identity Newsletter

© 2022 Operation Identity